Stories

Stories

The Long March

For those airmen who had been shot down, only to become prisoners of war (POWs), life in German prison camps was challenging. Prisoners typically faced cramped quarters, limited food, and monotony. As the end of the war approached, life in these camps was to become even tougher. Rations depleted as food supplies in Germany dwindled. The much-treasured Red Cross parcels arrived less regularly. Then, early in 1945, with the Allies advancing on both fronts, their German captors began a series of forced marches of POWs from camps located in Eastern Europe to the heart of Germany. These marches, conducted in extreme winter conditions, occurred in the four months between January and April 1945. Many POWS lost their lives. In an extraordinary first-hand account, New Zealander, F/Sgt Bernard (Bill) Allen, the only survivor of his crew shot down in 1944, recorded his experience of ‘The Long March”.

F/Sgt Bill Allen, (RNZAF 968734 / POW No. 380, Stalag Luft 7

(Credit Air Force Museum of New Zealand)

From a total of 257,000 western Allied prisoners of war held in German military prison camps, over 80,000 POWs were forced to march westward across Poland, Czechoslovakia, and Germany in extreme winter conditions, over about four months between January and April 1945.

One of these marches began on 19 January 1945 when 1,565 prisoners of war (POWs) from Stalag Luft VII, including Bill Allen, were sent on a 240km forced evacuation march to Złotoryja. The march began at 0630. Each man was issued with two-and–a-half days marching rations before leaving. No transport was provided for any sick who might have fallen out on the march and the only medical equipment carried was that carried by the Medical Officer and three Sanitators on their backs.

Conditions were bitter. Winter temperatures dropped below −20 °C. The prisoners were ill-prepared for the evacuation, many having already suffered from poor rations in captivity and wearing clothing ill-suited to the appalling winter conditions. They prisoners slept in cowsheds and barns overnight. Other times they marched in darkness through the night. They had to scavenge for food as they marched to supplement their meagre rations.

Three weeks later they reached Goldberg where they were crammed into cattle trucks for a train journey to Germany. By this time there were numerous cases of dysentery and facilities were totally inadequate. The majority had no water on the train journey for two days.

Their destination was to be Stalag III-A, located about 50 km south of Berlin. This camp already held more than 40,000 prisoners, consisting mainly of soldiers from Britain, Canada, the U.S. and Russia, in overcrowded and unhygienic conditions. Finally, as the Russians approached the guards fled the camp leaving the prisoners to be liberated by the Red Army on 22 April 1945.

According to a report by the US Department of Veterans Affairs, almost 3,500 US and Commonwealth POWs died because of the marches. It is possible that some of these deaths occurred before the death marches, but the marches would have claimed the vast majority.

Bill Allen’s log

New Zealander, F/S Bernard (Bill) Allen was Mid-Upper Gunner with the Bonisch crew of 75 Squadron that was shot down on a bombing raid on railway marshalling yards at Drex in Northern France on 10 June 1944.

Image: Bonisch crew

The Bonisch crew: F/S James Stuart Millar (Air Bomber), F/O Henry Herbert Marsh (Wireless Operator), F/S James Murdoch Thomas McKenzie (Navigator), Sgt. William Thomas Reaveley (Flight Engineer), Sgt. Frank William Cousins (Rear Gunner) and P/O Lester Lascelles Bonisch (Pilot). Photograph from the Wartime Log of Bill Allen.

(Credit: Air Force Museum New Zealand).

The only survivor, in captivity Allen began to write a log of his experiences, firstly of the mission itself and being shot down over France, then during the period when he was at large in France and afterwards as a prisoner in France and Germany.

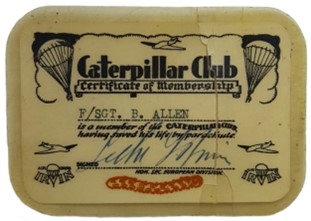

The Caterpillar Club membership card of Sgt Bernard ‘Bill’ Allen, sole survivor of the Bonisch crew.

(Credit: Katherine Walker).

Allen’s log concludes with his account of the march that he, and 1564 others were forced to undertake from Stalag Luft VII. Allen’s record of the long march is published here in full, having been published on the 75 (NZ) Squadron website https://75nzsquadron.wordpress.com/bill-allen-memoir/

15th January, 1945

Have just learned today that a new Russian offensive has opened in the sector opposite our camps. It is rumoured that the camp will be evacuated, but nothing definite has been heard.

17th of January

The Russians are coming up fast and we have been instructed to pack and be ready to leave at a moment’s notice.

18th of January 1945

Last night we had a Russian air raid in the town very close to the camp, it was very close and we are moving out in the morning.

(Editor: Bill did not write in his notebook again until 9th Feb.

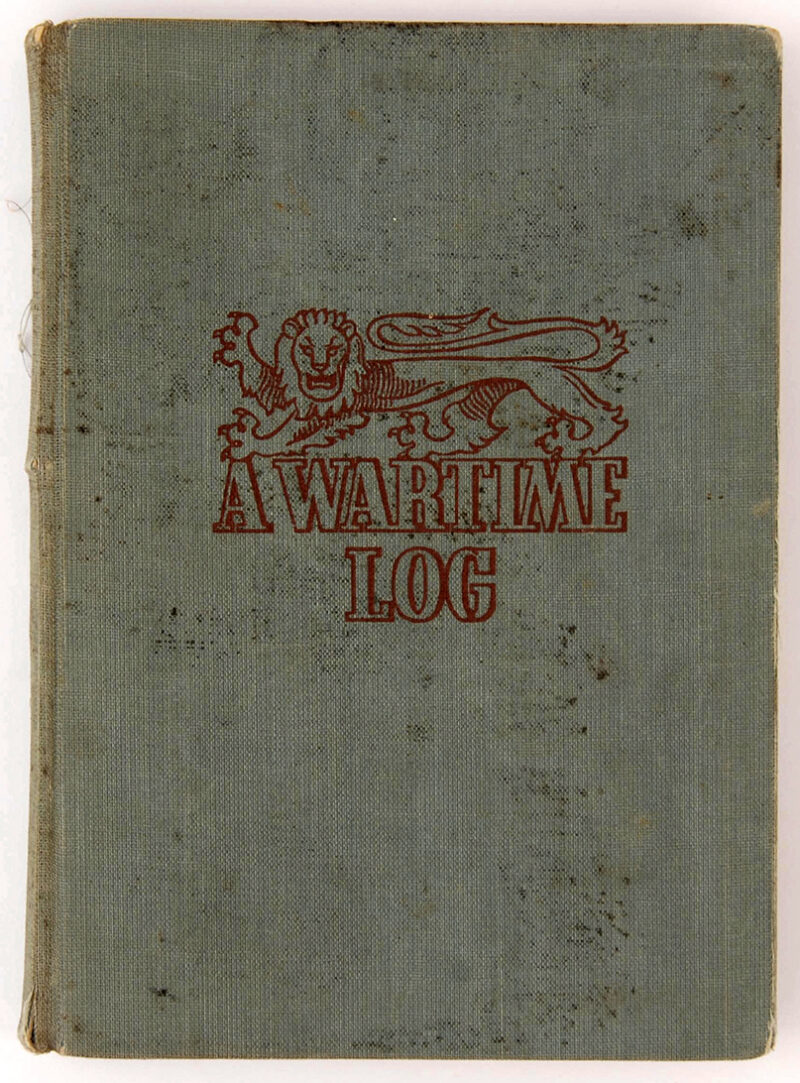

Image: Allen Diary

Caption: Flight Sergeant Bill Allen’s POW diary. (Credit: The Air Force Museum of New Zealand)

9th February, 1945

Little did I know what was before me when I last made an entry in this book, we have just experienced three weeks of hell. We left Bankau at 06.30 hours on Friday the 19th of January, it was snowing hard, and a high cold wind was blowing, we were told the temperature was 26° below zero, the roads were covered in ice and snow. Fifteen hundred of us set off to march to Sargan.

Our route on that first day took us from Kretzburg on the Polish border, through Konstadt to a village called Wintersfeld, there we were herded like sheep into barns until we could neither sit nor lay down. This was a terrible night, made worse by the fact that we were all very fatigued and badly needed a sleep, but it was impossible to obtain any. We had marched all through the day until dusk and had covered 24 kilometres (15 miles).

At a quarter past one, we were called out of the barns, fell in and told to march again as the Russians were coming up rapidly behind us, and we were less than a day ahead of them. The Germans marched us all through the night, and the next day. The latter half of the journey being through forests and up steep hills, so we were soon very exhausted, we were throwing away items of kit all the way along to lessen the load on our backs. In a very short time we had only the clothes that we stood in and our two blankets tied round our necks. One chap broke a leg in falling on the ice and was pulled along on a sledge by his crewmates.

This was one of the longest march of the whole period. We stopped again in a deserted brick factory at a village by the name of Carlsrue. However, we were not to get much rest this time, as the German Officer in charge informed us that the Russians were coming up so fast they were almost upon us, and the German Artillery were taking over the brick yard as a defence zone. At eight o’clock we started again, to march all through the night, and to make it worse a terrible blizzard blew up again. That night was a nightmare, our object was to cross the River Oder before the morning as the Germans hoped to make a stand there.

Men were dropping like flies and the M.O. and two Padres were working like n……. helping them along. We finally got across the river which is very wide at this point, at about eight o’clock in the morning. We were covered in snow and frost, and in a very pitiable condition. Here we were herded into a dirty old cowshed, stinking of dung and cattle, and had to lie on wet smelling straw. However, we were so fatigued that we were soon asleep. The total distance for the day and two nights of marching was 41 kilometres and 12 up to the brickyard, making a total in all of 53 kilometres.

We marched out again on the 21st of January to a place called Wanson, another 28 Kils. (17½ miles), here our food was exhausted and we were getting very hungry, we met Poles and Russians on the farms that we stopped at, and we were exchanging soap for potatoes. We met lots of people from German occupied countries, they were chiefly peasants working on the farms. I should have mentioned that all the farms are very large, and are state owned, the farmers live in a group of houses in the centre of the farming area, almost like a small town. There are great barns and cow sheds, and into these the Germans herded us after each day’s march. The Germans prevented us talking to the Poles and Russians as much as they could.

Food from the 22nd of January became so short, that we had to march only one day in two as the chaps were getting very weak and ill. Every place we stopped at we left a number of sick behind to be brought along on carts drawn by horses. By the way, due to the enormous shortage of fuel in Germany, the Germans used a tremendous amount of horse drawn transport, and what few trucks they used were only very essential military lorries; these burning charcoal and each towing as many as three smaller cars to save fuel. The roads from Poland were jammed with horses and carts packed with civilian refugees with their belongings. I imagine it was like France in 1940.

We saw a number of Russians that had joined the German Army when the Germans were on top, and these refused to fight when the great Russian armies commenced their latest attack. The Germans put them under guard again and put them with us. One very outstanding feature of the march was the shops that were closed in each of the towns, through lack of provisions to sell, especially food shops, these appeared to have been shut for years. The food situation in Germany is very bad, I don’t know how the armies carry on with the poor rations that they receive, and the civilians are in a far worse state.

The next few days of marching were very much the same, except that the food situation became more critical. We were cut down to 1/6 of a loaf of bread per day with half a cup of thin barley soup for which we had to queue for as long as two hours. The total mileage covered in the next few marching days was 62 ½ miles or 100 kilometres. The towns or villages that we stayed at were, Heidersdorf, Pfaffendorf, Standorf and Peterswitz.

From the last place names, our food ran out completely and we went three days on four bread biscuits. The English Medical Officer told the German Commandant that we could not march any further without food, but it did not make any difference, we still had to march. The German Officer told us that we may go the rest of the journey by train from the next town, this cheered us a little but we were not very hopeful. The German promises were not to be relied upon as we had learned many times before.

About this time, at a large road junction, on one of the now famous auto-bahns, we met another great column of English prisoners from a camp called Lansdorf, those poor devils had been bombed by the Russians in mistake for German barracks. There were one hundred killed and six hundred wounded, the others were evacuated.

At Peterswdtz, we learned that the Russians had captured Breslau so we were not to go to Sargon after all as the camp there was also being evacuated. The next few days were spent just marching ahead of the advancing Russians with no fixed destination, the prospects for us were very bad as we were by this time in a very bad condition through lack of food, and tramping the roads and living in cowsheds like cattle for endless weeks was a grim existence. In some of the farms the fellows were grovelling in cow and pig food for the tops of sugar beet and carrots that had lain under the snow for weeks and were rotten. Dysentery was rampant and the Medical Officer was having a terrible time.

Our next two days of marching took us to Prousnitz and then on to Goldberg where we were supposed to get on board a train, which prospect cheered the men considerably, but this proved to be just another of the Commandant’s idle and empty promises. We stayed at Prousnitz for two days and then marched out to Goldberg where we were again installed in a barn, this time in a very filthy farmyard, and where our awful predicament really reached a most grim state. The first thing, out bread ration was cut to an eighth of a loaf, and soup almost disappeared.

We looked a rough crowd by this time, we had been marching for sixteen days and were unshaven and in the most cases unwashed. We had not had our clothes off either day or night from leaving Bankau, many of the chaps were lousy through sleeping in dirty cowshed and barns. The worst part of the whole trip was the perpetual hunger which we were all suffering from. Men were exchanging gold watches, some valued at £15 and £20 for one small loaf of bread.

Australian POWs on the march through Germany by Alan Moore, RAAF official war artist (1945)

(Credit: Australian War Memorial)

5th February 1945

The seventeenth day on the road and a nightmare march through the night ended the marching. We had again been promised rail transport from Goldberg and had 10 K to march to get to the town and station. We left the farm in the middle of the night and we set off marching in a long weary straggling column, and after an hour we were caught in a fierce blizzard whilst out in the open and on top of a range of hills. It was terrible to see men collapsing in the snow and laying there until the Padre’s coaxed them to go on. We passed on dead man frozen in the snow; it made one think of stories we had heard of the Artic region. We passed lots of German Army transports stuck in snow drifts, some overturned, and Germans cursed us because we would not help them dig the trucks out.

We arrived in the Railway Station at eight o’clock the next morning and were herded into the box cars, 56 men to a truck and were packed in worse than in the barns, we could neither sit nor lie down, it was grim. We only travelled 200k’s (125 miles) but it took us three days. We stood as long as sixteen hours at a time in sidings with about two or three travelling in between, and worst of all, we had no food whatsoever throughout the journey on the train, the result being that we were all too weak to stand on arrival at our destination. It took us two and a half hours to stagger, I won’t say march, to the P.O.W. Camp, outside the town.

The Camp number was IIIA and was an old last war camp, at the moment containing 38,000 men and built for 8,000. There were French, Yugoslavs, Serbs, Italians, Poles, Russians, Americans and English prisoners in separate compounds. It was very much overcrowded, we were put into barracks meant to hold 150 men, 400 in each, it was almost as bad as the train.

At this camp we expected to get Red Cross Parcels, but there were none to be had, and hadn’t been for weeks previously. The German rations were also very poor, namely 1/24 of a 1lb. block of margarine, 1/5 of a loaf of bread and 1 cup of thin soup per day, the whole camp was in a state of semi-starvation. On arrival in the Camp, we were taken for a hot shower which we badly needed and when I had stripped off my clothes I was quite scared at the sight of my thin limbs and exposed ribs, I looked almost emaciated, it will take a long while to get our bodies built up and our strength back.

The whole twenty-one days of the marching was a grim nightmare which is best forgotten, but not easy to forget, and the sooner the War ends so that we can get home from this horrible camp, the better.

12th February 1945

A few words about IIIA. We have so little food that we can only lie on our beds all day and think of home and food, we have no energy for anything else. It is a large camp, divided into a number of smaller compounds each of these containing so many men. The Officers are in one, Americans, Serbs, Poles, French etc., in the others, yet they meticulously count us twice a day at 7.00a.m. and 5.00p.m. How they think anyone can escape heaven knows, there are about nine walls of barbed wire before you reach the outer fence, and there are hordes of armed guards all along the wire.

14th February 1945

We learned today that our bread is to be decreased again from today so that we now receive three ounces per day. If the War does not end very soon a lot of us will not survive this imprisonment, we are taking on the appearance of skeletons, I would not like my Mother to see me in this condition.

23rd February 1945

Since last making an entry in this book I have had seven days in bed (if you can call it a bed) with tonsillitis and flu, and due to our undernourishment condition I have had a rough time. The food rations are getting less, due we are told to the R.A.F. bombing of Berlin, which is only 25 miles away, and also to rail junctions in this area. Germany is in a grim state and I don’t know how they stand up to this pounding that they are receiving from the Allied Air Forces. A sensation was created by the British Camp Leader giving us each twelve cigarettes, the first since Christmas. It was a decided booster of moral.

27th March 1945

The moral of the chaps has received a great fillip at the news of Field Marshall Montgomery’s big drive in the West, and we are all beginning to see visions of an early finish to the War and our return home. The food in Germany has become worse during the last week. Our rations have again been cut very drastically by order of the German High Command. We now receive three thin slices of black bread, and a half lire of soup per day. Luckily a consignment of Red Cross food parcels came in, and we each received one this week, it will supplement the meagre German rations for a few days.

The area of this camp is about two square miles and is situated twenty-five miles from Berlin. The air-raid sirens are howling day and night as the R.A.F. and the Yanks bomb Berlin and Leipzig. The Germans in the principal towns of Germany must be bomb happy by now, we stand for hours every day watching dog fights between American and German fighters, it’s quite thrilling especially when great formations of Allied bombers fly over to bomb Berlin.

9th April 1945

News keeps on coming in every day of the Allies push in the West, and we are all looking forward to being released, as quite a number of P.O.W. camps have been already. It will be great to get home again, especially from the point of view of food. The rations are getting less every day, and the quality worse.

11th April 1945

Once again we have had the grim news that we are to be moved from the camp to another camp in Bavaria, near Munich, we are to go in the morning at 8 o’clock. The distance is so great and the railway service so bad that we don’t expect to get to 7A Camp inside two or three weeks, if at all, it is possible we may be cut off by the Americans in the Leipzig area.

Royal Australian Air Force Roadside rest: winter march from Sagan by A.H. Comber, enlisted RAAF (1945)

(Credit: Australian War Memorial)

12th April 1945

We marched down to Luckenwalde and boarded box cars on the Railway for our journey South. There were sixteen hundred of us, twelve hundred Officers and four hundred N.C.O.’s, all R.A.F. Air Crews, they seem to be hanging on like grim death to R.A.F. Personnel. However, the box cars will be better than another march like the one from Bankau, we are to be packed 40 in a truck like cattle.

15th April 1945

After two days hanging around at the Goods Yard at the Luckenwalde Station, we are back at the Camp again, as the Germans realised that they would be unable to move us to the new Camp due to the speed of the Americans advance on Leipzig. The Country is almost cut in half so it looks as though we will now remain in IIIA until we are taken by the Allies or Russians, who we have just heard have also launched a large scale attack on Berlin.

The two days that we were in the town were quite a pleasant change. The weather was good, and we were given a surprising amount of liberty, such as talking to the German civilians, and walking up and down the railway tracks. We were exchanging soap for eggs and bread from the civvies, soap being the only thing we have plenty of, and a thing of which the Germans are very short. A tablet of English soap will purchase the half of the town.

The Germans are getting very slack and easy with us now that it is near the end of the War, they know that they have lost and are doing their best to be friendly with the prisoners, but we won’t wear them. All the young men have been put in the front lines and only sixty year old Volk Sturm (Home Guards) guard the camp, some of them are almost too old to carry a rifle.

20th April 1945

Strong rumours are running round the camp that the Russian Army is within eleven kilometres from the Camp, so if it is true they should be here by the morning.

21st April 1945

Apparently the rumours were true regarding the Russians, as all the guards have got their kit packed, and are ready to move out this morning, some of them have gone already, and the remainder are more or less on their way.

We can hear the Russians fighting in the town already and the last of the Germans are leaving the camp. The k’g’s are breaking down the wire, and roaming all over the camp, great excitement is everywhere.

A Norwegian General has taken command of the camp, with an R.A.F. Wing Commander as second in command, guards were organized to prevent the food stores being looted by the Russian prisoners who have gone berserk.

The sky is full of Russian and German aircraft engaged in combat, it is very thrilling to watch but very dangerous, occasionally one comes down and strafes the camp, and it is not very funny, especially as the buildings are so flimsy and are no protection from cannon shells.

22nd April 1945

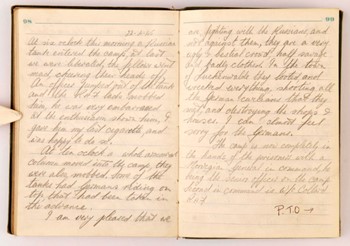

At six o’clock this morning a Russian tank entered the camp, and at last we were liberated, the fellows went mad, cheering their heads off. An Officer jumped out of the tank and the R.A.F. lads mobbed him, he was very embarrassed at the enthusiasm shown him, and I gave him my last cigarette, and was happy to do so.

At ten o’clock a whole armoured column moved into the camp, they were also mobbed. Some of the tanks had Germans riding on top, they had been taken in advance. I am very pleased that we are fighting with the Russians, and not against them, they are a very ugly, bestial crowd, half savage and very badly clothed. In the town of Luckenwalde they looted, and wrecked everything, shooting all the German civilians that they met and destroying the shops and houses. I can almost feel sorry for the Germans.

The camp is now completely in the hands of the Prisoners with great excitement everywhere. A Norwegian General in command, he being the senior Officer at the camp, and the second in command is W/Cmdr. Collard R.A.F.

The final written entry by Bill Allen, recording the events of 21 April.

While that completes Allen’s written record of captivity it is not the end of the story. Returning to New Zealand he gave his log to his sister, who provides the final instalment of Bill’s memoir:

When my brother Bill arrived home I was very thrilled when he gave me his Diary inscribed on the cover “Dedicated to my sister”. He explained that now he was safely home, he would finish writing it up for me, but as time went on he seemed less inclined to even want to talk about it so it remained unfinished.

However, on his first evening at home he did tell me what happened when the Russians reached the camp he was then in at Luckenwalde, just a few miles outside of Berlin. This is the final chapter as Bill told it to me.

The joy they felt when the Russians broke into the camp was very short lived and after a few hours’ freedom, they were very securely back in their huts and the camp had more armed guards around it than when it was in German hands. Bill did say that when the Russians stormed in they (the POW’s) ran out into the town but when they saw the very dreadful behaviour of the Russians they felt sick and went back into the camp.

The following day they were delighted to see a convoy of American Army trucks surround the camp and they cheered and shouted expecting to be released but their excitement turned to horror when they saw the American Officers in charge being escorted back to their armoured cars and all the convoy moved off again. The POWs couldn’t believe their eyes and the Russians wouldn’t tell them anything and treated them very badly.

This happened again on each of the next three days and on the third day Bill managed to squeeze through trees and bushes and up to the barbed wire where he got the attention of a black American truck driver parked just outside. He told Bill they had come to take the POWs to freedom but the Russians wouldn’t part with them.

The driver after talking to Bill for a while said he didn’t like the look of things and if any of them wanted to take a chance and ‘run for it’ he would be back during the night and help them because he didn’t trust the Russians and said he himself wouldn’t like to be in their hands and his officers were very worried about the POW’s. Bill told him he would like to risk it so it was arranged that the driver would come back at an arranged time during the night and bring what was necessary to cut the wire.

He told Bill his truck could carry 20 but not one more so it was up to Bill to arrange it with the POW’s. Enough of them gave their names to Bill to make up this number and when it was time to go he went quietly to each one to tell them but only 5 of them came with him. The others had decided they may be released the next day so they didn’t want to risk it.

On going to London for formal demob Bill met a chap from camp who told him it had been a further three awful weeks before the Russians would allow them to leave, during which time two of them (POWs) had been shot trying to escape the Russians. Very, very sad indeed.

My brother was always very unhappy because he was the only one of his crew to survive on 10.6.44.

Bernard (Bill) Allen passed away on 23 June 1994.

References:

- Report of a Forced March Made by Occupants of Stalag Luft 7, by Peter A.Thomson, Pilot Officer, RAAF – Camp Leader and D.C. Howatson, R.A.M.C – Camp Medical Officer, February 15th, 1945. Scottish Saltire Aircrew Association

- Annual report of the DVA Advisory Committee on Former Prisoners of War, in cooperation with the Department of Defense, 1999.

- Bill Allen Memoir from https://75nzsquadron.wordpress.com/bill-allen-memoir/