Operations

Operations

Operation Exodus – Bringing the POWs home

By April 1945, many Prisoner of War camps in occupied Europe had been liberated. Though free, the ex-prisoners were hundreds of miles from home with many suffering from illness, fatigue and starvation. As ex-POWs flooded into collection points throughout Europe, it was clear that a swift method of repatriation was needed. Consequently, RAF bombers were tasked to fly the POWs home. By 1 June approximately, 3,500 flights had brought 75,000 men back to the UK. Their return home symbolized not just the end of the war, but the restoration of their dignity and humanity.

Stirlings of 190 Sq. lined up to take on their passengers.

(Credit: Imperial War Museum)

With the war in Europe entering its final stages, in March 1945 planning began for the repatriation of the tens of thousands of POWs, who were then still held in a number of camps scattered across Germany. Initial thoughts were centred around seaborne transportation, but it soon became obvious that with the future availability of useable shipping ports still uncertain, this could potentially take much too long and be fraught with difficulties.

Inevitably some of the POWs would be in poor health and physical condition, making speed of the essence. Because of this the planning focus, which was shared between the British War office and SHAEF (Supreme Headquarters Allied Expeditionary Force), shifted from evacuation by sea to a huge airlift.

RAF Bomber Command: From Combat to Compassion

Operation Exodus, which began in late April 1945, was the RAF’s codename for the repatriation of Allied POWs from Germany and occupied Europe. This massive logistical operation involved the transportation of thousands of liberated servicemen, primarily British and Commonwealth forces, back to the United Kingdom from airfields in Germany, Belgium, and the Netherlands.

To do some of Bomber Command’s fleet of heavy bombers would be repurposed for humanitarian missions.

Ironically, the operation began on 26 April. That morning Lancasters returned from the RAF’s last significant heavy bomber raid of WW2, an overnight operation against the oil refinery at Tonsberg in southern Norway. On the first day of the airlift Lancasters of 50, 61, 463 & 467 squadrons repatriated dozens of POWs.

The spartan confines of a Lancaster had not been designed with passengers in mind. Flying with a smaller crew – no bomb aimer and a single gunner – to maximise the number of POWs per flight, each aircraft was able to carry a maximum of twenty-four POWs. Comfort was at a minimum, some blankets and cushions to soften the stark interior of hard metal surfaces.

Dennis Griffiths – a rear gunner with 7 PFF recalled that on 8 May many of his squadron went into Cambridge to celebrate the German surrender. Later that evening they were approached by R.A.F police in company with civilian police, asking which squadron we were from.

He recalled that the crew were directed to a waiting R.A.F coach and told us to board as they were required back at base. During the journey we speculated as to why, the consensus was the need to “sort out some pocket of resistance.”

Not so. Back at base they were told they would be flying to Lubeck, Germany to transport ex-POWs back to the UK. Griffith’s task was to make sure only twenty-four passengers were to board. “I was to allocate them sitting along the whole length of the fuselage and to make sure they remained seated in these positions.”

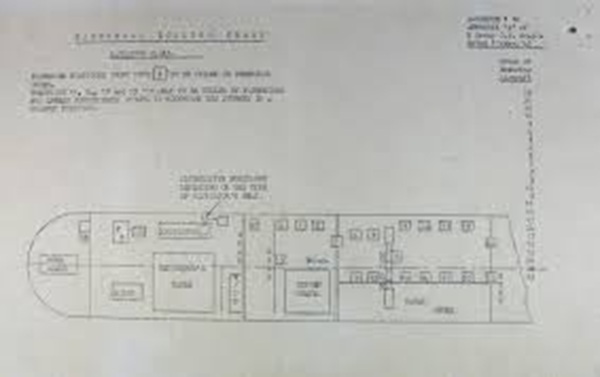

5 Group Loading instructions. These were extremely specific as to the number of passengers,

the order in which they would be loaded and where they would be located in the aircraft.

(Credit: National Archives of Australia)

Only later it became obvious why these instructions were given. A Lancaster taking off from Juvin Court with twenty-five ex-POWs positioned in the rear of the bomber, radioed back that it had to make an emergency landing. The distribution of the passengers in the aircraft had upset the flying trim causing the pilot to lose control. It crashed at Roye-Ami and tragically all crew and the twenty five passengers perished.

Griffiths described the mission. “We were awakened at 4am 9th May, took off with no parachutes. However we had 24 blankets and 29 Mae Wests (life jackets). On arrival at Lubeck we were delayed quite a while. Then all abroad, me carrying out my orders, landing at RAF Station Tibbenham that evening.

I saw our guests down the short ladder at the rear of the aircraft the look of joy on their faces, which more than compensated for our celebrations being cut short.”

On arrival they were processed by Embarkation Officers who were responsible for the ex-POWs welfare. Processing included disinfestation, feeding and the provision of adequate clothing and a pay advance. Each was provided with a pamphlet containing information regarding the reception centre and a welcome message from the King. In addition they were permitted to send a telegram or postcard stating, “Arrived safely, see you soon.”

The passengers on Griffith’s flight were approached on arrival by a number of medics carrying what appeared to be flit guns (hand-pumped insecticide sprayers). Each returning POW was squirted down the front and the back of the shirt and trousers. Then the medics beckoned over the crew. “We said, ‘no, we are crew.’ They replied ‘Yes, but you have been in their company.’ So we got the same treatment.”

The former POWs were marshalled toward a hangar. Music was playing from the Tannoy’s, and long row of tables full of food and beverages were laid out. Haven been woken at 4am for their mission and it was now late evening, Griffith’s crew decided to partake only to be told “No, ex-POWs only! You will be looked after when you get back to your home base. So be it, it was a most gratifying day. We were tired but we felt good.”

For the liberated servicemen, the journey home was both a physical and emotional ordeal. Many had spent years in captivity, surviving on meagre rations and enduring harsh conditions.

Their release and repatriation were moments of overwhelming relief and joy, tempered by the lingering effects of their experiences.

Former POWs make their way out to waiting 635 Squadron Lancasters at Lübeck, Germany, on 11 May 1945.

(Credit: Imperial War Museum)

There were more than three thousand repatriation flights in just 23 days. At the height of the operation the repatriation aircraft from Europe were arriving in England at a rate of sixteen aircraft per hour, bringing home over one thousand young men each day.

By the end of the operation Allied forces had returned over 354,000 ex-prisoners to Britain. 75,000 of them thanks to the efforts of Bomber Command.

For many of the New Zealanders who had been prisoners it had been a long wait for freedom. Most of the 8,348 Kiwi soldiers captured had been held since the early setbacks in Crete, Greece and North Africa in 1941 and 1942. Many were held in Italy until the Italian armistice in September 1943, when over 3,000 New Zealand POWs were transferred to Germany. There were also 575 airmen captured and 194 sailors.

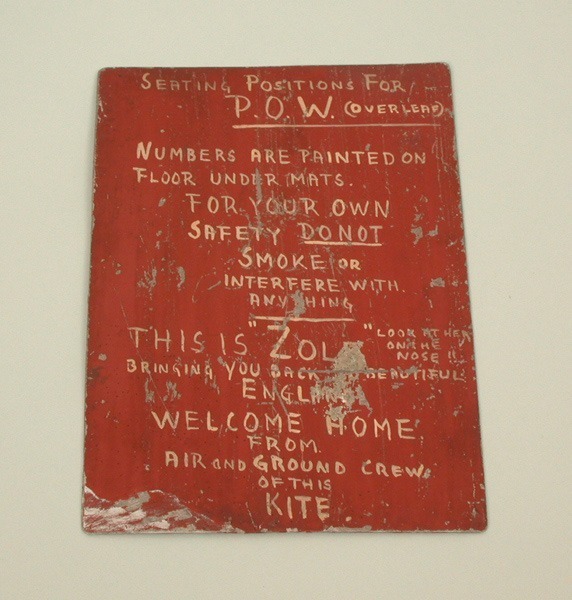

A surviving relic of Exodus – A welcome sign from the air and ground crew of Lancaster ‘Zola.’

(Credit: RAFStories.com)